Two months ago, six of the world’s largest multilateral development banks (MDBs), including the World Bank, released a Joint Report on Climate Finance providing an overview of international financial commitments to projects and programs designed to align with the objectives of the 2016 Paris Agreement. The report covers all MDB operations that support actions aimed at increasing mitigation and/or adaptation efforts approved during the 2018 fiscal year (July 1, 2017-June 30, 2018).

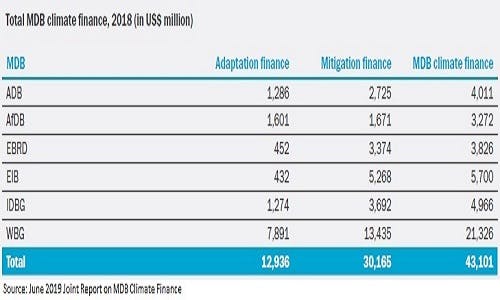

As the World Resources Institute wrote last month, if taken at face value, the report’s overall picture appears generally positive. Combined, in 2018, MDBs committed over $43 billion to climate-related projects, a 22% increase over 2017 and a 60% increase since the adoption of the Paris Agreement. For the World Bank’s part, its commitments accounted for nearly half of all MDB climate-financing, of which $15.7 billion came from its main concessional lending arms, the International Development Association (IDA) and the International Bank for Reconstruction and Development (IBRD). The World Bank exceeded its own target of 28% of new commitments for climate, articulated in the Climate Change Action Plan of 2016, by roughly 4%.

Before the Joint Report became public, the World Bank issued two press releases touting its “record-setting” contributions towards climate-related finance for FY18 and offered a few examples of projects resulting from its “institution-wide effort to mainstream climate considerations” into its development activities. Perhaps the most notable of the chosen examples is a project where financing was made available to help in the expansion of what is set to be the world’s largest solar installation, Egypt’s Benban Solar Park. According to the published release, this project was primarily led by the Bank’s private-sector arm, the International Finance Corporation (IFC), by “finalizing a landmark $653 million debt package."

In fact, the IFC itself only provided a portion ($202 million) of this financing; the rest was picked up by nine other financial institutions, with construction and technical assistance supplied by privately-owned European and Chinese firms.[i] While this risk-sharing is typical for projects of this size, one could easily be misled into thinking it was all IFC-financed.

Although IFC projects warrant more public scrutiny, public information is often not as complete as is for IBRD and IDA project listings. In researching IBRD/IDA climate-finance interventions, using disclosed project-level documents on the Bank’s website, we find numerous anomalous accounting practices that raise serious questions as to the Bank’s methodological approach in deciding what counts as mitigation and/or adaptation activities, and if double-counting, or over-counting has been avoided.

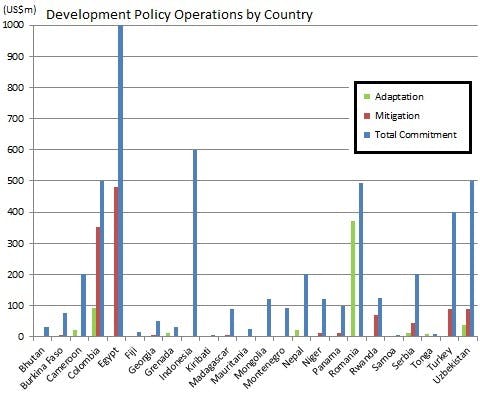

For example, an IBRD Development Policy Loan (DPL) for Egypt, the third of a series approved in December 2017, appears in the Bank’s climate-finance listing, and claims that $479 million, or 41.7% of its over $1 billion loan, is committed to mitigation.[ii] While available project documents relating to this loan do not reference the Benban solar project by name, they do allude to it, and further indicate that the policies initiated by Egypt under ‘prior actions’ for previous DPLs were responsible for its development.[iii] This DPL also specifically aims to support Egypt’s Feed-in Tariff (FIT) policy[iv], which was partly responsible for initiating private investment in the Benban project. Upon inspection of project documents, however, it is clear that not only was this loan approved after the IFC closing on Benban (which the DPL required), but that a much smaller percentage of its overall financing is eligible to qualify as mitigation finance, as defined by the Joint Report's annex on methods. In fact, “fiscal consolidation” is named as the primary objective listed for this loan, to be achieved by increasing taxes and reducing public-sector wages, improving the business environment through deregulation in investment laws and industrial licensing requirements, and “enhancing competition” by “restoring the viability of its domestic gas sector” and “opening the downstream gas sector to private investors.”[v]

Other Development Policy Operations (DPOs)[vi] listed as climate-finance projects by the World Bank include similar language for policy and institutional reform apparently unrelated to mitigation or adaptation.

In Turkey, a DPO suggesting “liberalization” of the state-operated rail system, “protection of industrial property rights,” and “making the labor market… more flexible” counted $88.8 million as mitigation activity. And in Serbia, a $200 million loan, set to close in August 2019, is regarded by the Bank as contributing over $56 million to mitigation and adaptation, even though the bulk of the project’s objectives are focused on “helping Serbia… transition from a planned to a market economy.”

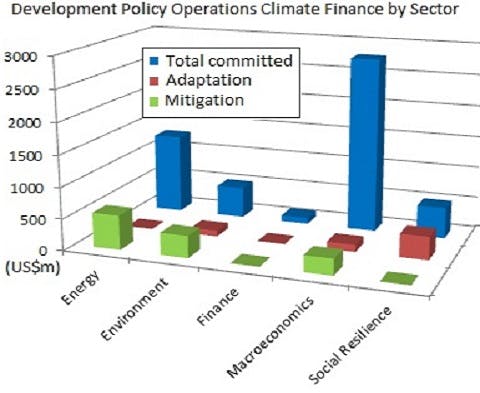

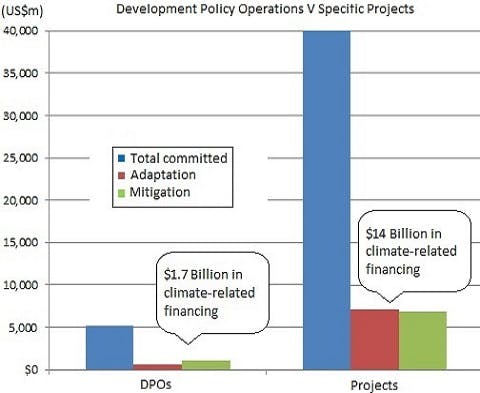

Most DPOs indicate that only a very low percentage of any one’s total financial commitment may be classified as climate-finance (more than half of the 26 DPOs count less than 40% of its total commitment as related to climate). Furthermore, DPOs as a category only account for roughly 11% of the Bank’s total climate financing, indicating that the Bank did not consider using policy reform as a primary instrument in climate action, but rather relied largely on specific project financing to address adaptation and mitigation.

Aside from DPOs, our preliminary review of World Bank climate-related finance also involved analysis of project-specific development, that is, development finance mobilized for the sole purpose of advancing a particular project, be it the construction of a road, a metro station, a transmission line, a clinic, a school, a water system, or a government-led program designed to alleviate poverty or boost agricultural production.

For FY18, the World Bank financed in whole or in part 303 such projects. Although listed under “climate finance,” 92 of those, approximately $8.7 billion, was, in the Bank’s specific project assessment, non-climate-related, leaving 211 projects that contributed, in some way, according to the Bank, to climate adaptation or mitigation. Although the World Bank has already entered its 2020 fiscal year, only 17% of the funding made available to those FY18 projects with a climate component has been disbursed thus far. Furthermore, non-climate lending far and away outstrips funding made available to adaptation and mitigation in the first place.

This brief review is not meant to provide a complete picture of the World Bank’s climate-related finance, but our preliminary analysis indicates a potentially flawed methodological approach which contributes to widespread inconsistencies in climate finance accounting and project design.

Big, game-changing renewable energy infrastructure projects, like the one at Benban, are urgently needed, and the World Bank Group ought to be applauded for helping to finance such a project at significant cost. However, in order transform our energy systems in the short time required to avert climate catastrophe, MDBs must dramatically increase climate-related, mitigation finance aimed at developing more projects like Benban. Further, DPOs, aside from instigating narrow, non-climate-related fiscal reforms, ought to be recognized as useful, if not critical, instruments in securing the institutional and policy reform that will make such projects possible going forward. In FY18, the World Bank committed over $7 billion to energy-related operations, but its mitigation financing amounted to only half that, with even less going directly towards renewable energy infrastructure.

So, what does the World Bank count as climate-finance? In a follow-up report, we will leave DPOs aside and examine the World Bank’s climate-finance operations at the project-level.

Notes

[i] See: https://www.reuters.com/article/egypt-solar-financing/update-1-ifc-and-banks-close-653-mln-in-funding-for-egypt-solar-plants-idUSL8N1N405W; https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=bipBGsUEZTk; https://www.constructionweekonline.com/projects-tenders/182367-egypts-37km2-benban-solar-park-set-for-mid-2019-operational-start; https://www.africaenergyinfrastructure.com/egypt-construction-begins-at-benban-solar-park/

[ii] See our January 2017 report on Egypt's DPF here: https://bankinformationcenter.cdn.prismic.io/bankinformationcenter%2F190cde67-9281-496a-a6be-ed888981de05_egypt-dpf-formatted-pub-1.6.17.pdf

[iii] ‘Prior actions’ is the phrase the WBG uses to describe conditionality; that is, actions (frequently legislation) that the recipient government must take before loans, grants, or credits for development operations are made available.

[iv] Feed-in tariffs (FiT) typically provide a guaranteed price premium above the electricity market price and guaranteed purchase of a minimum amount of power by utilities. Egypt’s FiT covers solar and wind power.

[v] Project documents for this loan may be found here: http://projects.worldbank.org/P164079/?lang=en&tab=documents&subTab=projectDocuments

[vi] DPLs, DPFs, and DPOs are institutional rather than project-specific. See: http://siteresources.worldbank.org/PROJECTS/Resources/40940-1244732625424/Q&Adplrev.pdf